Were sauropods swimmers or walkers?

Footprints give clues about the activities of the giant dinosaurs

An international team of scientists, led by the China University of Geosciences in Beijing and including palaeontologists from Liverpool John Moores University, has shed new light on some unusual dinosaur tracks from northern China. The tracks appear to have been made by four-legged sauropod dinosaurs yet only two of their feet have left prints behind.

Previous studies of such trackways have suggested that the dinosaurs, which were far too big to walk on their hind legs, might have been swimming. Scientists agree that dinosaurs could swim – nearly all animals can – but evidence for swimming has been disputed. It has been suggest that trackways in which only the front or hind feet are imprinted into the sediment could have been made by swimming dinosaurs, their bodies buoyant in deep water while they paddled along with their arms or legs.

Now, a new study of fossil trackways from Gansu Province in northern China has provided evidence that some hindfoot-only tracks were produced by walking, not swimming animals.

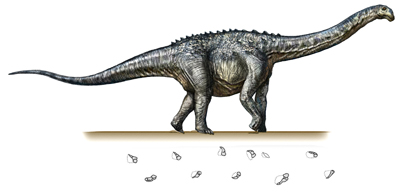

The tracks, dating from the Lower Cretaceous, over 120 million years ago, are roughly circular and with a clear set of four or five claw marks at the front. These prints are matched perfectly by the feet of medium-sized sauropod dinosaurs, massive long-necked, plant-eating dinosaurs such as Brontosaurus and Titanosaurus.

But how could only the prints of the hind feet be preserved?

Lead author Lida Xing said: “Nobody would say these huge dinosaurs could stagger along on their hind legs alone – they would fall over. However, we can prove they were walking because the prints are the same as in more usual tracks consisting of all four feet, it’s just that here, we don't see the hand prints. If they had been swimming, with the hind legs dangling down, some of the foot prints would be scratch marks, as the foot scrabbled backwards.”

The tracks are well preserved, but there is evidence the animals were walking on soft sand. They pressed down because of their weight, and the claws dug deeper so they could gain purchase in the sediment. Most of the animal’s weight was towards the rear, and so the hind-feet pressed deeper. The front feet on the other hand, did not apply enough pressure to make a lasting mark.

Co-author Dr Peter Falkingham, of LJMU’s School of Natural Sciences and Psychology, said: “Footprints can be a really great source of information about extinct animals like dinosaurs, as they are made by the animal in motion. Unfortunately, footprints are also very complex, and factors such as the sediment the footprints are made in can affect their shape and consequently how we interpret them. This is a great example of how a relatively simple motion – making a footprint in sand, has implications for what we think these animals were doing.”

The paper is appearing in Scientific Reports.

Images courtesy of CHEUNG Chung Tat (Hongkong, China).