Stars’ odd behaviour gives up hidden black holes

Black hole hunters are turning detective to uncover hidden behemoths in Space.

Astronomers discovered a small black hole outside the Milky Way by looking at how it influences the motion of a star in its close vicinity.

The method could be key to unveiling many more unseen black holes in the Universe and help shed light on how these mysterious objects form and evolve.

“Similar to Sherlock Holmes tracking down a criminal kingpin by the strange movements of their ‘associates’, we are looking at every single star in this cluster with proverbial a magnifying glass trying to find some evidence where the real power lies,” says Dr Sara Saracino from the Astrophysics Research Institute of Liverpool John Moores University.

'Dynamic' detection method

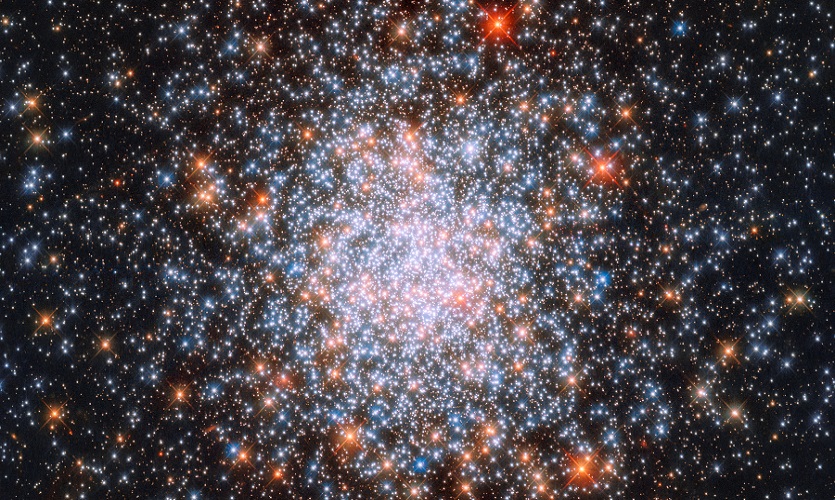

Using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, the astronomers discovered the new black hole lurking in NGC 1850, a cluster of thousands of stars 160,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighbour galaxy of the Milky Way.

The research published today (Thursday, November 11) in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society is the first time this ‘dynamic’ detection method has been used to reveal the presence of a black hole outside of our galaxy.

Astronomers have previously spotted such small, “stellar-mass” black holes in other galaxies by picking up the X-ray glow emitted as they swallow matter, or from the gravitational waves generated as black holes collide with one another or with neutron stars.

However, most stellar-mass black holes do not give away their presence through X-rays or gravitational waves. “The vast majority can only be unveiled dynamically,” says Stefan Dreizler, a team member based at the University of Göttingen in Germany.

How do black holes grow?

“When they form a system with a star, they will affect its motion in a subtle but detectable way, so we can find them with sophisticated instruments.”

The detection in NGC 1850 marks the first time a black hole has been found in a young cluster of stars - only around 100 million years old – and the team say that by comparing them with larger, more mature black holes in older clusters, astronomers may understand how black holes grow.

The team used data collected over two years with the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) mounted at ESO’s VLT, located in the Chilean Atacama Desert.

“MUSE allowed us to observe very crowded areas, like the innermost regions of stellar clusters, analysing the light of every single star in the vicinity. The net result is information about thousands of stars in one shot, at least 10 times more than with any other instrument,” says co-author Dr Sebastian Kamann, at Liverpool’s Astrophysics Research Institute.

This allowed the team to spot the odd star out whose peculiar motion signalled the presence of the black hole.

Data from the University of Warsaw’s Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment and from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope enabled them to measure the mass of the black hole and confirm their findings.

ends

The team is composed of S. Saracino (Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, UK [LJMU]), S. Kamann (LJMU), M. G. Guarcello (Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, Palermo, Italy), C. Usher (Department of Astronomy, Oskar Klein Centre, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden), N. Bastian (Donostia International Physics Center, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, Basque Foundation for Science, Bilbao, Spain & LJMU), I. Cabrera-Ziri (Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany), M. Gieles (ICREA, Barcelona, Spain and Institut de Ciències del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain), S. Dreizler (Institute for Astrophysics, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany [GAUG]), G. S. Da Costa (Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia), T.-O. Husser (GAUG) and V. Hénault-Brunet (Department of Astronomy and Physics, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Canada).